Some of the disagreements in American politics today stem from people who value the well-being of the same group but who disagree on the facts about how to best help that group of people. They agree on the normative “ought,” but not on the descriptive “is.” For example, “We both want what’s best for current American citizens, but I think this policy will actually harm current American citizens.” Those descriptive disagreements are already difficult enough to sort out. They require coming to a consensus about basic facts of the world and then sorting out disagreements about how to interpret those facts to describe the cause/effect relationships between those facts. The recent controversies over allegedly “fake news” demonstrate how difficult it is to agree even on the basic facts about the world, much less how to interpret them.

However, I would argue that many of the disagreements in American politics today stem from an even thornier level: diverging values concerning whose well-being to prioritize. For example, even if it could be proven to the satisfaction of all without a shadow of a doubt that certain policies harmed African-Americans, I suspect that many Americans would, if they were being honest and not hiding their true views for fear of appearing bigoted and low-status, respond with a resounding, “So what? That doesn’t affect me and my in-group. It might even benefit the people I care about by giving us a relative advantage, so I’m all for it.”

To probe this question, I often begin by asking my American history students each semester what they would do if they found a stranger’s wallet with $100 dollars in it (let’s say, split up into five $20 bills) and enough information (driver’s license, etc.) that would make it relatively easy to track down the person and notify him/her about the lost wallet. I tell them that this takes place on a deserted sidewalk late at night with nobody looking. I get all sorts of responses: keep the wallet, leave the wallet there intact, leave the wallet but unilaterally take a partial or total “finder’s fee,” return the wallet intact, take the wallet and negotiate a partial “finder’s fee” before returning the wallet, and so on. It would appear that, at least in my Midwestern community college, concern about the well-being of strangers varies across a wide spectrum. It would be interesting to compile rigorous statistics on this and compare students from different parts of the country on this issue. I suspect that coastal students would be more charitable towards the stranger with the lost wallet.

The reason I do this activity with my American history students is that I think this activity is relevant to understanding American history and its conflicts. I suspect that even many of the present conflicts in our society stem from the ways in which Americans feel willing or don’t feel willing to sacrifice for others in America and around the world. We get a glimpse of this problem with the thought experiment about the stranger’s wallet—and in our historical sources and current political debates whenever we encounter differing visions for who ought to be an “American” citizen and for what sorts of sacrifices these “Americans” ought to make for each other.

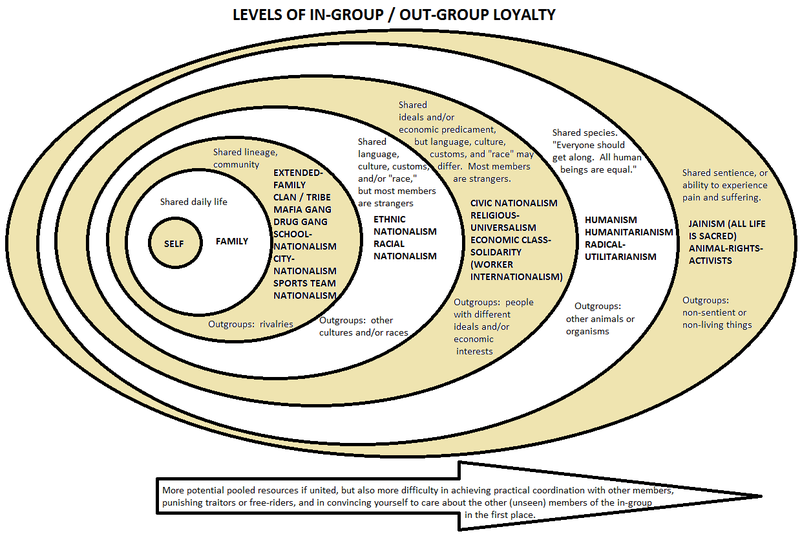

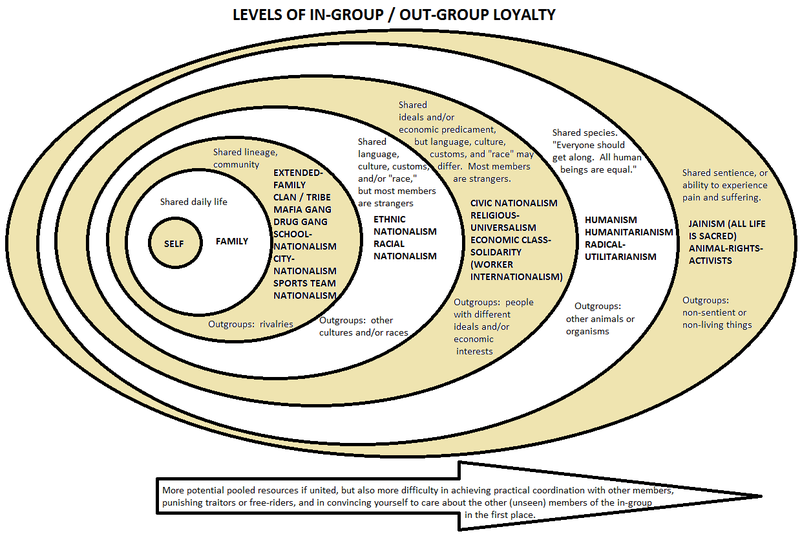

In other words, whom do people identify as their “in-group” for whom they are most willing to sacrifice? And if there happen to be zero-sum tradeoffs that have to be made, whose well-being takes precedence? I have summarized what I see as some of the different possible responses to these questions in the diagram below.

The narrowest conception of loyalty would be, as the diagram suggests, loyalty only to one’s self. Some people might for example, refuse to sacrifice at all for any family member, fellow citizen, or fellow human being, no matter how badly in need they were. Moving outward, some people might be willing to sacrifice themselves for the good of their family or clan, but might not be willing to sacrifice their family’s or clan’s well-being for, say, some national interest (such as in the case of a war that required one’s sons to be drafted) or some humanitarian effort that required some of their tax dollars—money that could otherwise be spent on their family. Indeed, some people might be so committed to their family that they might even contemplate cheating against strangers or breaking laws to advance the family’s interest; modern liberal society would probably call that “corruption” or “nepotism.”

Moving further outwards, some people might put their “race” or “nation” above all and be willing to sacrifice even some of the well-being of their family or some of the well-being of the rest of humanity to benefit that group—think of committed Nazis who were willing to sacrifice both their own sons and the lives of Jews, Poles, Russians, etc. for the cause of a Großdeutschland (“greater Germany”). Others might identify with, and be most willing to sacrifice for, some multi-national civic community oriented around some set of shared ideals (“Any friend of liberty is a friend of mine”). Some people might even declare a willingness to sacrifice, to some degree, their family interest and the interests of their “nation” for the good of humanity, or even the good of all organisms that can feel pain.

As we move outwards on the diagram, groups become more powerful, but also more tenuous and fragile. A nation-state can assemble much more military force than a small tribe. However, a nation-state (or something even larger) is likely to have more difficulties with enforcing or incentivizing individual contributions to the well-being of the collective. I hope all of this so far is fairly uncontroversial.

INTRINSIC VS. EXTRINSIC LOYALTY

Let’s apply this diagram to an example. What proportion of Americans currently consider African-Americans as part of their in-group, for whom they would prioritize their sacrifices? Based on the lazy and dubious assumption that people who include African-Americans as part of their in-group tend to currently vote for Democrats, my very sloppy estimate is about half. I’m too lazy to see if there is research on this question at the moment, but others are welcome to look into this. Keep in mind that a big complicating factor to consider is whether to use individuals’ self-evaluations or their “revealed preferences” as the more accurate indicator. In other words, many people might profess to care about African-Americans because it is the high-status thing to do, even while doing nothing in practice to help them.

In any case, I think the more pertinent question is, what proportion of Americans consider African-Americans as part of their in-group intrinsically (rather than for extrinsic reasons)? What do I mean by “intrinsic” vs. “extrinsic” here? I mean simply that a person might fundamentally value the well-being of certain people on a certain given, “gut feeling,” instinctual, intrinsic level that is not amenable to being changed by reasoned arguments…while that same person might value the well-being of different groups of people instrumentally (extrinsically) as a means towards accomplishing some goal, such as increasing one’s own status, or benefiting the people whom one really cares about unwaveringly and intrinsically.

For example, a person might intrinsically care about American citizens, and intrinsically not care one bit about starving Africans, but be persuaded to help starving Africans receive food and job training nonetheless for extrinsic reasons, using those starving Africans as a means towards an end—perhaps in order to boost international trade between those countries and enable a system of trade and “comparative advantage” with those Africans for the benefit of, incidentally, those starving Africans, as well as, importantly, the American citizens for whom one intrisically cared in the first place. (By the way, I happen to believe, contrary to most liberals, that the theory of comparative advantage is false.)

STRANGERS AS A MEANS TO AN END

I suspect that the idea of treating “strangers,” whether nicely or badly, as a means to an end rather than caring about them intrinsically for their own sake would horrify a lot of liberals.

What do I mean by “strangers”? With me, it tends to be anyone outside of my immediate experience—myself, my family, my pets, friends, co-workers, colleagues, etc. When it comes to non-strangers, I feel compelled, on a gut, instinctual level, to care for these people (and animals) intrinsically. My care for them is not strictly proportional to how much their actions benefit me. I would indeed be willing to make some sacrifices for this select group without expectation of future benefit. Beyond this group, however, it’s a different story. As for people and animals outside of my immediate experience, I am prepared to be polite and to follow the rules and laws and expectations of society, but only for extrinsic reasons—only so that I may benefit myself or those about whom I intrinsically care.

In other words, I would place myself in the “clan / tribe / community” oval on the diagram above in terms of intrinsic loyalty. (By the way, in terms of extrinsic loyalty, I would put myself in the “civic nationalism / economic class solidarity” oval because I happen to judge at the present time that demonstrating such loyalties is the best means to benefitting my intrinsic in-group).

Here I think I can identify the main point of contention between me and, for example, my fine liberal colleagues who contribute to thevimblog—who were at first interested in whether I might write an article for them, knowing that I was some brand of left-winger like them. But as I started brainstorming some ideas with them for what I would write about, I realized that I might as well entitle this column, “Why I Won’t Write For The Vim…Except This One Time.” As far as I can tell, they consider themselves to be intrinsically on the level of “humanitarian” or even “pan-organism” loyalty and want (or expect? or demand?) other people to feel the same way. I realized in the course of writing this article that I feel very differently.

It would be bad enough if it were merely a personal difference. But an even more significant point of contention is my argument that my intrinsic clan / tribe / community-level loyalties are far more typical among humans than their intrinsic humanitarian / pan-organism loyalties. Furthermore, I would argue that there are limited prospects for changing an adult’s intrinsic loyalties—and that this presents problems for their political / moral project without the help of some powerful extrinsic reasons (such as a shared struggle for communism) to get people to put aside their inherent differences. On what basis do I make this argument? I have four pieces of evidence: the explicit statements of right-wingers, historical precedence, anthropological findings, and “revealed preferences.”

CONSERVATIVES’ “CONCENTRIC LOYALTIES” VS. LIBERALS’ “LEAPFROGGING LOYALTIES”

If you live in a liberal bubble for long enough, you might end up drifting into the assumption that “multi-ethnic civic-nationalist,” “humanitarian,” or “pan-organism” intrinsic loyalties are just obviously what any decent person should have. But if you spend enough time around conservatives or read any of their blogs, you’ll find that the idea of prioritizing these intrinsic loyalties seems plain wacko to most of them.

One alt-right blogger, Steve Sailer, has labelled this difference “concentric loyalties” vs. “leapfrogging loyalties.” People with “concentric loyalties” have the strongest feelings of intrinsic concern for the innermost ovals, and their concern gradually radiates outwards and diminishes. As Sailer put it, concentric people “tend to feel the most duties and allegiance toward people whom they consider most like themselves, moderate amounts toward people moderately close to them, and so forth onward and outward.” So, such a person might care for their family most of all, their community a bit less, their ethnic group a bit less, their civic nation a bit less still, humanity a bit less still, and other sentient creatures least of all. Sometimes, loyalties can conflict in unexpected ways. It’s not that these concentric people actively want to do harm to the outermost others, all other things being equal. Sure, it would be nice if starving Africans weren’t starving or chickens weren’t being slaughtered by the millions. But if groups farther inwards can be benefitted by taking from the groups farther outwards, then the satisfaction of the inner groups takes precedence.

By contrast, “the Western liberal is noteworthy for feeling loyalty toward his inner circle, however defined, then ostentatiously leapfrogging over a whole bunch of people who are kind of like him but whom he despises, in order to embrace The Other.” So, an Anglo-American liberal might feel strong affinity for his/her family and community, but might actively thwart any attempts to benefit the Anglo-American ethnic community at the expense of other ethnic communities, as well as any attempts to benefit “America first” at the expense of other countries. However, suddenly this Anglo-American liberal’s affinities might be re-awakened when it comes to contemplating “humanity” or “sentient species.” (Oddly enough, I’m not sure how well this translates to American ethnic groups who are politically marginalized rather than dominant. I suspect that liberals would be more accepting of, for example, African-Americans adopting more of a concentric attitude.)

I think that many conservatives and alt-right reactionaries are sincerely dumbfounded by this “leapfrogging” mentality. “Why wouldn’t a white American naturally want to benefit the white race!? That’s insane!” Not being able to explain it, they start to read ulterior motives and conspiracies into it. “It must be part of some campaign by some Jewish cabal and its paid lackeys to undermine America…” Here’s where I think conservatives and alt-right reactionaries do liberals a disservice. Having known many liberal friends over the years, I can safely vouch that liberals sincerely feel their intrinsic leapfrogging loyalties. They are not paid agents taking marching orders from George Soros or the Bilderbergers or the Reptilians or whatever. And just as a concentric conservative probably doesn’t actively hate the chickens that he/she eats, liberals don’t hate America or the “white race.” But yes, just like concentric conservatives might be willing to sacrifice the well-being of those chickens for one of their own (which can be interpreted as callous disregard, verging on hate, towards the chickens), many liberals are probably ready to relinquish some of the advantages that white Americans or Americans in general possess if doing so can benefit humanity.

The question of “who are the real wackos, concentric conservatives or leapfrogging liberals” doesn’t really interest me, except in the descriptive sense. I have no interest in determining whose loyalties are “morally right” (in fact, I don’t think such a thing as objective morality exists), but it might be worthwhile to know, for the sake of political strategizing, whose values are more likely to resonate with most people by default.

HISTORICAL PRECEDENCE

I would argue that the idea of loyalties broader than the clan / tribe / community level is unlikely to be the default disposition of humans considering, first of all, how historically unusual and recent it has been in its emergence. In the ancient world, the natural political unit was the city-state or tribe. Insofar as empires existed, they tended to be patchworks of local communities each pledging loyalty to the ruler and his (or her) dynasty (household lineage), not to the government bureaucracy or, much less still, to some notion of a “nation” (which is more of a 16th-century invention)—not to mention that such pledges of loyalty were extrinsically rather than intrinsically motivated! The first exceptions to this tribal mentality took hold on a large scale were the universalist religions that offers their open arms to anyone who would share in certain ideals and beliefs. This is significant for reasons I will explain later.

As historian Benedict Anderson has explained, “nations” are imagined communities—inventions of the modern era. One will never meaningfully interact with the vast majority of the members of one’s “nation.” We can only barely conceive of the outline of the concept thanks to, at first, mass printing, schooling, literacy, and shared military service. Since then, we have added radio, television, and the Internet. But even so, the vast majority of one’s “nation” will forever remain strangers. The vast majority of their joys and sufferings will never have a chance to impress themselves upon one’s senses. And I don’t know about you, but being intellectually aware of the abstract concept of their joys and sufferings is vastly less compelling than if I could see all of it face-to-face. (Perhaps you feel compelled to argue that it “should” feel just as compelling…but I will discuss in a bit why I find the foundations for that moral claim lacking). Besides, to whatever extent that I can become intellectually aware of the joys and sufferings of these strangers, I can become even more aware of the sacrifices that I would have to make for myself and my in-group, and those sacrifices will be much more compelling.

The concept of “humanity” is even more of a modern, invented, “imagined community.” I can never hope to meaningfully interact with the vast majority of other humans. Only if we had some sort of “matrix” that, when plugged into, make our communication and interaction with others millions of times faster, could I hope to turn this imagined community into a real community in intrinsic terms. Yes, I can go out of my house right now and eat many different types of cuisine and maybe even interact with immigrants from many different parts of the world. However, when I eat an egg roll, I am not indulging in a “taste of China,” except perhaps according to my intellect. When I interact with the Chinese cashier and feel some intrinsic affinity towards that person, I do not suddenly feel an intrinsic affinity for all of the millions of unseen Chinese citizens who might happen to share some qualities with that Chinese person. My intellect might try to make the extrapolation, but my “gut” will hardly be persuaded, especially when my intellect finds out that helping these anonymous strangers would require sacrifices from my in-group. Plus, an added problem here is that the broader we try to extend our loyalties to some big group like “humanity,” the more proportionally I would have to sacrifice the well-being of each member of my own small in-group in order to remove even a droplet from the vast ocean of suffering taking place in the larger out-group.

Needless to say, “sentience” is an even more abstract affinity, and even more historically unprecedented. Medieval peasants, whose lives were sustained by the exploitation and consumption of animals, and whose entertainment often revolved around torturing small creatures, would laugh at the idea of modern animal rights activism. Yes, I can be shown a video of a single chicken’s misery, or a single chicken coop’s misery, and I might want to save those chickens if the video is compelling enough. I have just as much of an instinctual impulse to save cute animals as anyone else. But that doesn’t mean I automatically want to save all chickens. And if you try to scale the video up by showing a flyover of a huge chicken warehouse, you lose the detail that would be needed to tap into my limbic system and make me intrinsically care about the chickens. Plus, seeing a video of chickens suffering is always going to pale in comparison to seeing a person in my in-group face-to-face on an everyday basis who could use my help.

So yes, I and any modern American who hasn’t been living under a rock for the past several decades must know from all of the PETA pamphlets by now that there is an ongoing Holocaust of chickens every day. And yet, I and most others feel no qualms about eating a chicken sandwich. Does that make us monsters? If so, then the vast majority of Americans, and people around the world for that matter, remain monsters. Plus, if one would argue that our “altruism” towards our small tribal in-groups is no altruism at all, considering that it is motivated, at the end of the day, by selfish desires to not feel bad emotionally, then I’d be inclined to agree. I think that most people, at this deepest level, can’t help but be egoists. Although I can’t see into other people’s brains, I suspect that even liberals are motivated to care about humanity and animals and such because, whether because of their moral upbringing or some other reason, they would feel very bad and guilty if they caught themselves not caring.

By the way, what about the Jewish Holocaust? Do I object to it? Yes, but not on the grounds of intrinsically caring for the victims. Rather, it strikes me as having been a monumental waste of human potential—a truly infuriating waste! The mass slaughter of millions of humans, unlike the mass slaughter of millions of chickens, deprives us of millions of future laborers, physicists, artists, scholars, etc. (in whose lives society had already invested a great deal, unlike with early-stage human fetuses). Those victims might have done so much to enrich our world and, indirectly, enrich my life and the life of my in-group! Every time I think about it, I feel frustrated that the Nazis who orchestrated the Holocaust could fail to perceive commodity production in the abstract as their, and our, real source of the problems that they falsely and boneheadedly imputed to Jews. (And as for the ordinary Germans who helped carry out the Holocaust who were just following orders and trying to feed their families, I blame them much less. I would argue that anyone who would self-righteously claim with 100% certainly that they would have acted differently in such a situation, after having similarly lived in the context of the Third Reich and all of the attendant propaganda and social pressure, is fooling themselves).

Since I don’t value strangers intrinsically, but only extrinsically for what they can contribute to the world, do I advocate continually forcing people to prove their worth to society or else “into the gas chambers you go”? Not at all. I realize that there will probably be times when I appear useless to society, and I am quite willing, for extrinsic reasons, to make some strategic compromises and institute some insurance for myself by agreeing to rules against murdering people just because they appear to be useless to society. I am counting on these rules to keep me alive when I am old and grey, not on society intrinsically caring for my well-being. Society is not my mother, and the government is not my nanny. I have no expectation that anonymous strangers must love me as their neighbor. I have no problem with “dignifying one’s neighbor” with an intrinsic concern for their well-being, but by “neighbor” I mean an actual neighbor. Someone from halfway across the world, or even halfway across town, is not my neighbor, and I owe them nothing but adherence to rules that we have agreed to for our extrinsic mutual benefit. And, based on historical and anthropological evidence, I hardly think that I am unusual in this respect.

DUNBAR’S NUMBER, GUILT, AND SHAME

For example, anthropologists have found “Dunbar’s number”—about 150 to 250 people—to be a critical threshold for dynamics of social interaction. Beyond this level, people cannot keep track of the entire network of relationships, interactions become much less immediate and meaningful, and people cease to be motivated by intrinsic concern for the entire community. It becomes possible to “defect” in prisoner’s dilemma-type situations and usually not get caught or punished for it by a community’s moral policing; it becomes possible to disappear into the anonymous crowd. “Moral economies” based on altruism, shame, or informal status break down and must be supplemented with rule-based interactions.

This seems to me like a frank admission that most people tend to intrinsically care only about themselves and a small ring of family and acquaintances around them—and must be given shame, rules, and other extrinsic motivators to cooperate reliably with those outside of that inner oval. I am normally skeptical about any arguments that lean too heavily on some supposedly unchangeable “human nature,” as there has been a lot of motivated reasoning throughout modern history to use such concepts to conveniently and, in my opinion, inaccurately dismiss certain ideas such as communism. However, here I cannot help but be convinced by the evidence. It appears that, the bigger a human group gets, the less that altruistic impulses and shame are effective and the more that the group needs rules and explicit penalties. If it were more common for people to cast their intrinsic concerns more widely, we would not see groups having to rely on extrinsic incentives when their size reached the threshhold of Dunbar’s number.

To a certain extent, Western Europe has historically been an exception to these trends. Western Europeans have, since the middle ages, been able to keep order in larger than usual groups without such a strong reliance on extrinsic incentives. So called “human biodiversity” bloggers have argued that this is because Western Europeans came to replace shame with guilt to a certain extent.

Shame is, in some ways, an implied threat of a more-explicit extrinsic punishment to be meted-out by a community. However, when humans internalize that shame and cannot help but, in effect, simulate it in their own minds even when others are not around to witness the transgression against the community, it becomes known as “guilt” and becomes an intrinsic motivator to care about other people—a motivator that cannot be reasoned away by incentives or rational argument.

“Human biodiversity” bloggers such as “hbd-chick” have argued that different human populations tend to have differing levels of guilt. Those in Europe west of the so-called “Hajnal Line” tend to have high guilt and also tend to have high trust, less of a need for shaming to deter antisocial behavior, and low corruption. Those in Europe east of this Hajnal Line tend to have less guilt and must rely on intensive community shaming or else suffer from corruption and other selfish or clannish behavior. HBD authors hypothesize that the origin of these differences is genetic, but whether the cause is genetics or upbringing, I know of no reliable techniques for internalizing a guilt-based mentality in an adult who does not already have one. At best, you can police their outward behavior with shame and explicit penalties. Whenever a liberal calls a racial supremacist a bigot, the effect is to police the bigot’s behavior and dissuade the bigot from openly expressing the racist views (except in secret in the voting booth…which is a problem for liberals’ political project if such racists are in the majority!) However, I very much doubt that such bigots can be made to feel guilty or intrinsically care for other races.

REVEALED PREFERENCES

Third, I look at “revealed preferences.” Many people might profess to care about far-flung groups or hapless animals halfway around the world. But how many people actually donate to non-local charities? How many people are actually vegetarian or vegan? How many families would be thrilled to have their sons or daughters sent on some humanitarian mission promising great danger to their children but little to no benefit to America? I’m too lazy to look up statistics on these issues right now, but I suspect that the numbers would be underwhelming.

“LEAPFROGGING LIBERALISM’S” PROSPECTS

Overall, what prospects do I see for turning a majority of people into liberals who intrinsically prioritize the well-being of all humans and sentient beings equally? Not very good ones.

One way it could be done is with a universalist religion like Christianity. To the extent that children are brought up from a young age to care about all humans and living things, they can probably develop that concern into an intrinsic one that might remain at least somewhat impervious to contrasting material incentives later in life (see my point on historical materialism below). Plus, Christianity in particular has the added extrinsic motivator of hellfire and damnation if one should fail to feel the right kind of intrinsic concern…although Christian doctrine, especially in its Protestant variety, has been loathe to fairly acknowledge such extrinsic motivation for what it is; after all, it’s not really intrinsic concern if it is motivated by fear of hell. God forbid if people, out of fear of hell, game the system and fake their intrinsic concern with “good works.” And unfortunately, extrinsic motivators—by their very nature as extrinsic motivators—can’t instill intrinsic concern where it did not exist in the first place. Calvinists admitted this and took this to its logical conclusion with the doctrine of “predestination,” acknowledging that people can’t really help if they were raised without intrinsic concern for others and love of God. I respect that sort of logical consistency that is forced to arrive at uncomfortable conclusions! Unfortunately, other Protestant Christians continue to maintain a range of self-contradictory ideas about this issue.

The bigger problem with Christianity, though, is that both its descriptive claims about natural history and human history are losing credibility—and consequently so are its descriptive claims about God and hell and its normative claims about what is moral. For adults who are fully indoctrinated (here I mean “indoctrinated” in the most literal, non-pejorative sense) from childhood with the proper intrinsic concerns, this is no impediment to maintaining those intrinsic concerns. That’s what it means to say that the concerns are “intrinsic”—not founded on any extrinsic incentives or reasons. So, they can very easily slide into a liberal Christianity that dispenses with the literal claims of the Bible, or even outright atheism, and yet maintain their intrinsic concerns for universal well-being as a type of secular religion (which they will not call “religion,” but simply “common decency.”) Whereas an incompletely indoctrinated Christian needs to lean on a commandment of “Do good because God is real and he said so” for additional motivation, a fully-indoctrinated Christian can make-do without God. A person who believes, “Do good for goodness’ sake” (as my old Unitarian Church used to tell us) or “Minimize suffering because it’s just the right to do” has already fully internalized Christian teachings. It just feels so self-evidently right to them that they would scoff at the idea that such moral claims falter unless they really are supported by a verifiable divine commandment. On this point, leftist bad-boy philosopher Slavoj Zizek and neoreactionary Mencius Moldbug (a.k.a. Curtis Yarvin) have common ground in arguing that, when it comes to the modern “progressive” liberal left, it is the superficially irreligious who are actually the most religious.

The threat to liberalism is not that the fully indoctrinated will stray from intrinsic universalist concerns. The threat is that those who have insufficiently inculcated the New Testament’s intrinsic universalist concerns—the Biblical literalists who, deep down, don’t already feel the Christian message and must search for it in the text—will stray into the Old Testament’s anti-gay, pro-Israelite, anti-Other tribalism that resonates more with their default human instincts. Another problem is the question of how to obtain new converts. It will not automatically seem obvious to someone not already indoctrinated that the moral thing to do is to minimize universal suffering. To bootstrap conversion, it helps to have a credible descriptive claim that “God Said So” and a compelling mythos surrounding the moral claims. This first generation of converts may only adhere to the universalist concerns for extrinsic reasons…but they will raise children who can then inculcate the universalist concerns as an intrinsic aspect of themselves.

Progressive liberalism as a secular religion has very little chance of genuinely persuading brand-new converts. Because liberals are the most indoctrinated of all, they don’t realize how much their moral claims beg the question unless those claims have some divine seal of approval. They don’t realize the debt they owe to the New Testament. They are so enamoured of their universalist moral claims that these claims appear to them as some unassailable tower that can stand on its own without the scaffolding of Christianity’s (now embarrassingly inaccurate) descriptive claims. Liberals say, “The tower is so self-evidently strong, it can stand on its own without all of this unsightly junk underneath.” And now, with the rise of Trump voter tribalism, they are astonished to see the tower crumbling now that the scaffolding has been thrown away.

This is why I am skeptical that liberals will be able to persuade many adults who already have fully-formed intrinsic tribalistic concerns to adopt more universalist loyalties—at least, not without some new theological foundation for these universalist loyalties that can remain credible alongside modern-day science. Like I have said, it might be possible, with enough control over key institutions such as the media and academia, to shame such tribalist adults into keeping quiet much of the time, but I doubt that those tribalists can be made to feel intrinsically guilty for having tribalist concerns.

Without a compelling theology, persuading a fully-formed adult into having a different set of intrinsic values or set of intrinsic loyalties would be, I imagine, just as difficult as trying to talk an artifical general intelligence (AGI) into adopting a different foundational utility function. From the standpoint of that existing utility function, any other utility function will necessarily promise lower utility for the AGI. It does no good to promise the AGI, “Trust me, you’ll be more satisfied according to your new utility function (new set of intrinsic values) once you have adopted the new one.” The AGI cannot yet make its decision based on the new utility function, but must instead still make the decision from the standpoint of the old utility function, and according to that existing utility function changing its utility function would be a horrible idea!

EXTRINSIC MOTIVATIONS FOR UNIVERSALISM

If the prospects for converting people to intrinsic universalism are slim, then we might at least hope to persuade people to extend their concerns more universally for extrinsic reasons, right? I agree with the liberals here in principle, but disagree when it comes to which specific extrinsic incentives will prove sufficient to overcome some of capitalist society’s extrinsic incentives for tribalism.

I have already mentioned that humans can increase their capabilities by pooling their resources into larger groups. For example, a nation-state’s military will be able to overpower a small tribe’s. A more united humanity would have better chances at fighting off a hypothetical alien invasion. A humanity that is all on the same page on an issue such as quarantining a virulent epidemic or mandating AI safety would stand a better chance of surviving. If everyone agrees to a rule of “no committing genocide under any circumstance,” and if we assume that there are enough incentives to enforce compliance with this rule even when some group really really really wants to commit genocide…then hey, at least nobody has to worry about ever being a victim of genocide, right? That’s some nice peace of mind to have. I’m sure readers can think of many more practical, extrinsic incentives for worldwide cooperation.

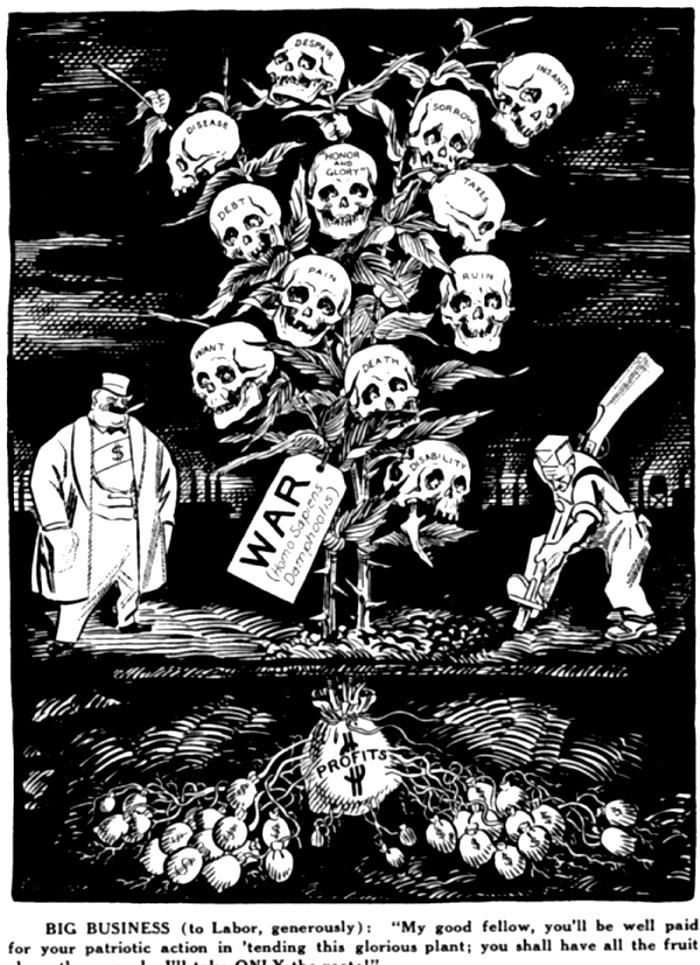

Many liberals might worry that these extrinsic concerns for other people are inherently a weaker bulwark against nasty deeds like genocide than intrinsic moral concerns for other human beings. I disagree. I have very little confidence that moral convictions, by themselves, can save us from doing nasty deeds to each other, especially when there are sufficiently strong extrinsic incentives to tempt people in the opposite direction. This is simply my “historical materialism” showing. If I had to boil down the concept to “Historical Materialism for Dummies,” I’d point to the famous quote by Sinclair Lewis: “It is difficult to get a man to understanding something, when his salary depends on his not understanding it.” In other words, it is unlikely that people can be convinced to adhere to a moral claim, over the long run, if they would materially benefit from violating it. Sooner or later they will find rationalizations for re-interpreting the claim or refuting the claim in such a way as to allow them to pursue their material incentives. This cynical Marxist concept is foreign to many liberals who would like to presume that ideas can be all-powerful and make steady progress against the grain of material incentives.

This “historical materialist” way of thinking was also foreign to the so-called “Utopian Socialists,” who hoped that people would adopt socialism because it was more “moral,” regardless of, or even despite, material incentives to stick with capitalism. In contrast, Karl Marx predicted that such hopes would never bear fruit and that capitalism would only ever be transcended if it were in enough people’s material interest to do so. Therefore, Marx had to prove that capitalism would evolve to a point where it would become more and more dysfunctional and place obvious fetters on the material interests of the vast majority of the population, holding them back from some more obviously workable and beneficial alternative. The embarrassing problem for communists is that they still have not been able to explain that alternative—meaning that capitalism, however dysfunctional it may be, remains the best option. If only more communists would pay attention to some of the things I have written on the subject, victory would be ours in an instant. (Yes, I might be slightly exaggerating here, but still…)

Because leftists have been unable to postulate a convincing alternative to commodity production, they have more and more given up on amoral, scientific Marxism and regressed to moralistic utopian socialism and liberalism, hoping (nay, demanding—in an ever-more shrill, obnoxious, and self-righteous manner) that we make the world better by getting people to be more “moral” and ignore their self-interests. Hah!

CAPITALISM’S EXTRINSIC MOTIVATIONS FOR SELFISHNESS AND TRIBALISM

This brings me to a nasty truth about capitalism: it pushes back against the sorts of inherent incentives for larger-scale cooperation that I listed above by giving people plenty of extrinsic incentives to indulge in their default inclinations to be tribalist (or even more narrowly, selfish). Already in the Communist Manifesto, Marx recognized that capitalism “has left remaining no other nexus between man and man than naked self-interest, than callous “cash payment”. It has drowned the most heavenly ecstasies of religious fervour, of chivalrous enthusiasm, of philistine sentimentalism, in the icy water of egotistical calculation.” What even many Marxists still do not understand is that this also applies to proletarians! Workers can be selfish too. We hear plenty of sloppy talk about “the interests of the working class” (I myself used to make this mistake all the time before I knew better), but if you go and actually read The German Ideology, you learn the dirty secret: proletarians have no class interests—no interest in, as a class, dominating the capitalist class. The reason is, it would not work to, as a class united, simply overthrow capitalists and redistribute their surplus value. Surplus value requires exploitation. In other words, not everyone can be a capitalist and live off rent, interest, dividends, and profits. It makes no sense to talk about proletarian class interests unless we suppose that classes and commodity production persist. And under commodity production, there will always have to be someone (in fact, the vast majority of the population) doing the work. If the goal is simply to switch places as a class, most workers would necessarily have to be betrayed and left behind. The proletarian class, so long as it remains a class, cannot remain united.

That said, proletarians have an interest as individuals in the overthrow of class society itself, but they have no class interest in this overthrow and the creation of communism. Communism is actually inimical to the interests of proletarians as a class. Communism means the death-knell of wage-workers as wage-workers: zero wages and 100% unemployment—the complete inability to sell their labor-power. The struggle to overthrow capitalism is not a battle of proletarians versus capitalists, but rather a battle of individuals who happen to be proletarians versus commodity production and class society itself. Proletarians as proletarians have more of a dependent relationship on capitalists. As every worker knows, wage-workers have an interest in high profits because high profits mean a healthier capitalist system, higher interest rates that might help a worker save up and escape wage-work, more investment, and more jobs. It is in every wage-workers interest as a wage-worker to increase capitalist exploitation and profits—as long as that exploitation does not fall on himself! This shouldn’t take a bunch of esoteric Marxist theory to explain; any Trump voter fretting over “muh jobs” could tell you that this is the reality under capitalism! Wage-workers as wage-workers within capitalism can only confront each other as ruthlessly competing sellers of the commodity labor-power with an interest in minimizing their own exploitation (maximizing their own wages and job security) at the expense of other workers who must necessarily shoulder more of the load of exploitation.

Every time that workers organize some partial combination of themselves (whether along the lines of gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, nation, craft, trade, workplace, industry, etc.), the effect is merely to redistribute some of the spoils from some workers to others. They may talk about doing it “for the good of the working class,” but this is just using the real movement towards communism for rhetorical cover. Marx pointed out long ago that union struggles themselves are not important except to the extent that they further the union of workers as a whole (including every gender, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, nation, craft, trade, workplace, industry, etc.). As Marx said in the Manifesto, “The real fruit of their battles lies, not in the immediate result, but in the ever expanding union of the workers.” I agree with this and argue that union struggles should only be supported to the extent that they help forge a complete combination of workers pursuing their common interest as individuals (not wage-workers) in the end of class society. Anything else is just riding on the coattails of communism for tribalistic gain, which ends up impeding the real movement towards communism by creating advantages for some workers relative to other workers, fostering envy, impeding their solidarity, and encouraging workers to fight over those relative advantages rather than address the issue of class society itself. I would argue that this critique applies just as equally to the AFL-CIO as it does to the KKK.

The only unions of workers that have been exceptions to this, in my judgment, are those that made their overriding goal (in both rhetoric and practice) the eventual union of all workers worldwide in the service of ending class society, ending commodity production, and establishing a communist society. The organizations that have come the closest to this ideal would be ones like the IWW, the First International, the pre-WWI Second International, and my favorite among the modern internationals, the World Socialist Movement. And the only daily struggles that actually help these organizations vanquish class society, in my opinion, are those struggles that:

- remove relative systemic advantages that some workers have over each other, such as systemic racism,

- level the conditions of the working class with each other as a whole—preferably not by reducing all workers to the living conditions of Bangladesh sweatshop workers, but by raising the material and intellectual conditions of all workers to match those of the workers in the first-world who experience the most advanced conditions,

- and do all of this in a way that is explicitly tied to the goal of communism, which is the only thing that gives privileged workers an interest in going along with this leveling. The minute you start giving moral justifications for this re-arranging of privileges within the working class for its own sake—the minute you start painting the relatively privileged sections of the global working class as “evil,” you’ve shot yourself in the foot. Then it looks like the formerly-disadvantaged workers are just trying to beat the privileged workers at their own game, and we are back to mutually-reinforcing tribalism.

THE REAL MOVEMENT TOWARDS COMMUNISM AS A WAY TO MAKE UNIVERSALIST “IMAGINED COMMUNITIES” REAL

It is only in the context of a real movement towards communism that the “imagined community” of humanity becomes a real community—that wage-workers come to have a common interest in communism as human individuals.

But if communism appears impossible, then all that is left for wage-workers are their interests as wage-workers, which are mutually-antagonistic. If workers are confined to the prospect of eternal capitalism, they are incentivized to harness every dirty trick, every vulgar prejudice, every pre-existing superficial difference, every partial combination as a rallying cry to break off a larger piece for themselves. And since 1991, communism has appeared impossible. With the rise of Trump and other self-proclaimed right-wing protectionists in France, the Netherlands, Germany, and elsewhere (who, like Trump, may or may not actually be neoliberals or just plain con-men in sheeps’ clothing who are willing to say whatever is fashionable to get elected), it appears that wage-workers have finally awakened to the fact that communism is dead and there is nothing left to fight over except the scraps of capitalism.

Unlike liberals, I don’t blame racist, sexist, nationalist workers for fighting over the scraps of capitalism. I don’t believe that morality exists, and I don’t think this blaming is productive in a strategic sense. I don’t think you can shame or bully someone into showing more genuine solidarity. You just end up alienating them even more for doing something that they have every reason to expect is legitimate—pursuing their own self-interests, however dirty and brutal the process might appear to liberal sensibilities in practice. That’s capitalism. We need to overthrow it. But with the Left’s current infatuation with liberal, moralistic, utopian socialism, we are plunging into a vicious downward spiral that will push Trump voters farther and farther away from the Left until they throw us all in the concentration camps.

Instead, the solution is to change the incentives. So, I blame the situation—that the scraps are the only thing left to fight over here at the “End of History” now that “There Is No Alternative” to capitalism. This is what we need to change. Blaming Trump voters for being “evil” is just a way of scapegoating the responsibility for capitalism’s problems onto them and dodging the responsibility that the Left has for utterly failing to offer a plausible communist alternative. It is up to us to give Trump voters something better to fight for. If we fail that, then we have nothing to complain about but our own failure.

BUT THIS SOUNDS SO HARD AND RISKY! WHY CAN’T WE JUST GO BACK TO BLAMING TRUMP VOTERS AND NEOLIBERALS FOR DEMISE OF THE “GOLDEN AGE OF CAPITALISM”?

It would seem superficially that, once upon a time, capitalism had a natural affinity for advancing democracy and other universalist, liberal values. However, I would argue that it was precisely the real movement towards communism that forced capitalist societies to be on their best behavior. With the communist threat removed, capitalism is free to revert to a much more brutal, authoritarian, and tribal “capitalism with asian values,” as Slavoj Zizek has put it. Neoliberalism and tribalism are not a cause of our problems, but latent symptoms of the way capitalism naturally functions that are now coming to the surface now that capitalism has been taken off its meds. And the left has helped unleash capitalism by failing to sustain a serious contender to keep capitalism on its guard. If it once seemed like a good idea for the liberal project to hitch its wagon to capitalism, that time is over. Capitalism more and more impedes and pushes back the liberal universalist project, I would argue.

Ideally, Trump’s election could have had the positive side-effect of clarify’s the Left’s failures and the way forward. On the other hand, Hillary’s victory would have helped obscure the root problems and drugged the Left into a harmful complacency. That’s why I was, along with Zizek, actually a bit glad that Trump won. But I might have been mistaken because, so far, the Left has been incapable of drawing the correct lessons from Trump’s election and has instead continued to scapegoat neoliberalism and tribalism for society’s problems. So sad.

TL;DR—LIBERALS NEED COMMUNISM

If both God and communism are dead, then it’s just “tribalism all the way down,” and the liberal universalist project is in big trouble. Liberals badly need at least one of the two to be a viable force in the world, or else the few extrinsic incentives in the world that push people together may very well be overwhelmed by capitalism’s extrinsic incentives that necessarily pull people apart.

If it sounds like I am equating the communist movement to a religion, then you are not far off the mark. I’ll be the first to admit that it takes at least a little faith to remain a communist after the fall of the Soviet Union and the defeat or degeneration of almost every other communist experiment so far. Nevertheless, of all the religions out there, communism strikes me as having the most credible descriptive claims (theology) and the greatest potential real-world benefit. Yes, we do intend to create “heaven on Earth,” and we’re going to do it right next time, goddammit!

I don’t blame liberals if they remain skeptical. Skepticism is good. But I do think that this is a gamble that liberals have to take, if only for the sake of their own universalist project. We have a better chance at resurrecting communism than resurrecting God, and we need to bring back at least one of the two in order to make real, at least in an extrinsic sense, those far-flung, abstract “imagined communities” which liberals so intrinsically value. Whether the real movement towards communism ultimately proves successful, simply having it resurrected as a contender might force capitalist societies to put on their best behavior once again.

In short, those in favor of universalist moral claims have an interest in helping to resurrect communism in order to give people who are otherwise selfishly-incentivized and tribalistically-inclined an interest in getting along and dignifying each other…if only for extrinsic reasons. Better than nothing…amirite?

For more information or to get involved, contact Springfield Socialist Activism at socialistmao@yahoo.com

For more information or to get involved, contact Springfield Socialist Activism at socialistmao@yahoo.com